OTC

Surface tension

In OTC

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

With an increasing number of people in the UK living with a skin condition, good treatment advice from pharmacists has never been more important

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you should be able to:

- Identify skin diseases associated with atopic eczema

- Advise on how they should be treated

- Explain the importance of the different microbiomes on the skin

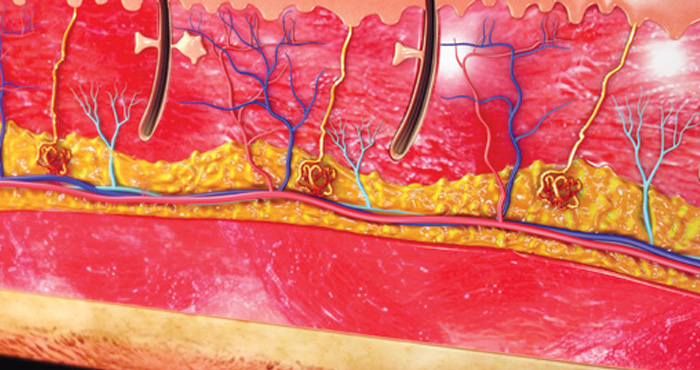

ATOPIC eczema (AE) is a common skin condition, affecting up to 20 per cent of children and around 3 per cent of adults. It is a chronic, relapsing and remitting condition. Although the cause remains uncertain, there are at least three possibilities:

- Barrier function abnormalities

- A dysfunctional immune system

- An altered skin microbiome.

As a consequence of these multiple potential pathologies, research suggests that patients with AE have a greater risk of developing several related skin conditions. This article provides an overview of these conditions, and how pharmacists and their teams can help support affected patients.

Barrier function defect: associated problems

Ichthyosis vulgaris

The term ‘ichthyosis’ comes from the Greek word ichthys, meaning fish. Ichthyosis vulgaris (pictured right) is an autosomal dominant inherited condition (it can develop if a single parent carries the abnormal gene) that affects one in every 250 children. Although not present at birth, ichthyosis develops within the first year of life and by five years of age, most sufferers have the condition. There are at least 20 different forms of ichthyosis, although the inherited form accounts for around 95 per cent of all cases. Ichthyosis tends to improve in the warmer months and normally worsens during colder weather.

The term ‘ichthyosis’ comes from the Greek word ichthys, meaning fish. Ichthyosis vulgaris (pictured right) is an autosomal dominant inherited condition (it can develop if a single parent carries the abnormal gene) that affects one in every 250 children. Although not present at birth, ichthyosis develops within the first year of life and by five years of age, most sufferers have the condition. There are at least 20 different forms of ichthyosis, although the inherited form accounts for around 95 per cent of all cases. Ichthyosis tends to improve in the warmer months and normally worsens during colder weather.

Presentation

Clinically, ichthyosis presents with symmetrical scaling, which can range from almost invisible roughness to large areas of dry scaling, particularly on extensor surfaces of the limbs, the centre of the face and the scalp. It resembles fish scale, hence the origin of the name. Bear in mind that both the palms and soles of the feet exhibit skin thickening (hyperkeratosis), which can lead to painful fissures, and there is a risk these fissures can become secondarily infected.

Causes

Ichthyosis is a genetic disease due to a loss-of-function mutation in the filaggrin (filament aggregating protein, FLG) gene. Filaggrin plays an important role in the production of natural moisturising factor (NMF), a collection of water-attracting amino acids and related compounds that maintain skin hydration. FLG mutations lead to reductions in NMF. Research has also confirmed an increased risk of AE in this instance and the development of other atopic diseases such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Advice and treatment

Patients with ichthyosis have increased scale formation and treatment is directed at removing this excess scale. Frequent moisturisation is important to prevent the skin from cracking, which can be painful, and it is advisable to use a soap substitute when washing.

Rather than using separate products, some emollients such as those in the Epaderm range are designed for complete emollient therapy (i.e. a single product that can be used as a soap substitute, a wash in the bath/shower and a leave-on product), which is clearly much more convenient for patients.

Keratosis pilaris

Keratosis pilaris (pictured right) is an extremely common skin condition that peaks at puberty, affecting 50 to 80 per cent of adolescents and continues in up to 40 per cent of adults. It has a slightly higher prevalence in women, the obese, type 1 diabetic patients, and can worsen during pregnancy and after childbirth. It is more commonly seen in those with AE and other atopic diseases (e.g. hayfever and asthma).

Keratosis pilaris (pictured right) is an extremely common skin condition that peaks at puberty, affecting 50 to 80 per cent of adolescents and continues in up to 40 per cent of adults. It has a slightly higher prevalence in women, the obese, type 1 diabetic patients, and can worsen during pregnancy and after childbirth. It is more commonly seen in those with AE and other atopic diseases (e.g. hayfever and asthma).

An autosomal dominant condition, a family history of KP is observed in nearly 40 per cent of cases. Many patients find that KP improves during the summer months but worsens over the winter period. Fortunately, for most patients, the condition is self-limiting and tends to improve with age.

Presentation

KP presents as 10 to 100 white or red keratotic papules 1-2mm in diameter with varying degrees of perifollicular (i.e. surrounding the follicle) inflammation. The affected skin has a rough, dry and bumpy texture that resembles gooseflesh and it is often colloquially referred to as ‘chicken skin’.

Although KP can occur on any hair growing area of the body, in up to 90 per cent of cases it presents on the outer and upper arms, thighs and buttocks. In a small number of cases, KP is seen on the chest, face and eyebrows. The majority of patients are asymptomatic although some may experience mild pruritus. It is often perceived by people more as a cosmetic nuisance than a specific medical problem.

Causes

Under normal circumstances, keratinous material within follicles is exfoliated (i.e. shed) but in KP there is follicular hyperkeratosis (an excessive production of keratin within the hair follicles). This keratinous material accumulates and ultimately blocks the follicular orifice, leading to the observed papules. The underlying reason for the hyperkeratosis remains unclear although one theory, which accounts for the association with AE, is mutations in the FLG gene, which leads to a defective skin barrier.

Advice and treatment

KP cannot be cured but is controllable with treatment. Pharmacy staff should reassure patients that KP doesn’t generally require treatment as it often resolves over time. For those seeking treatment, milder cases can be managed using emollients containing the keratolytic agents lactic acid or salicylic acid.

An emollient containing either of these serves a dual purpose: removal of the follicular plugs and increased skin hydration. Lactic acid modulates keratinisation, whereas salicylic acid leads to reduced cohesion between keratinocytes. The humectant urea also has keratolytic properties and is effective, particularly in combination with salicylic acid.

Commercial washes containing exfoliating agents may be of value but gently rubbing the affected areas during showering with an exfoliating pad or pumice stone is likely to be equally effective for unclogging the blocked follicles.

Summary

- There are at least 20 different forms of ichthyosis

- Patients with ichthyosis have increased scale formation

- Keratosis pilaris cannot be cured but is controllable with treatment

Supporting patients with their skincare

With GPs less likely to prescribe skincare products, pharmacies have the opportunity to build their business by helping customers to understand how to manage their skin, says Deborah Evans, managing director of training company Pharmacy Complete.

When considering the most appropriate treatment for conditions such as dry skin, stretch marks and scars, always establish more about the background to an individual’s condition, what is likely to motivate them when managing it and provide reassurance. Questions to ask include:

- What does their skin condition look like? (To understand the skin’s appearance, texture and colour)

- How long have they been experiencing the problem? (To understand whether this is a long-term problem or if there is a new trigger, as well as how recently it formed)

- How does the skin feel? (To understand whether it is itchy or painful)

- How does their skin change after exposing it to certain situations, such as cleansing or washing and what makes it better/worse? (To establish a cause of dry skin conditions).

Having a detailed knowledge of the types of ingredients that go into making a skincare formulation can help you recommend suitable products. For example, glycerin to boost hydration; shea butter to nourish and moisturise. Niacinamide B3 can help protect the skin’s moisture barrier, while urea helps to smooth and soften, and chamomile to soothe and calm.

Finally, self-care advice should cover healthy diet and exercise, the importance of hydration, avoiding sun exposure and harsh ingredients such as sodium lauryl sulphate, and the importance of massaging in skincare products regularly in gentle circular motions.

- New patient resources on dry skin and education for pharmacy teams on scars and stretch marks are available from Bio-Oil.

Contact dermatitis

There are two forms of contact dermatitis:

- Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), which is due to a hypersensitivity reaction after exposure to an allergen

- Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD), which arises from the direct effects of an irritant on the skin.

Irritant contact dermatitis is more common, accounting for nearly 80 per cent of cases of contact dermatitis.

Some evidence indicates a greater prevalence of positive patch tests (i.e. that they have allergies) in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) and the association between ACD and AD is thought to arise because of an impaired barrier function, which permits the entry of allergens and leads to possible further breakdown of the skin barrier.

In contrast, ICD is related to filament aggregating protein (FLG) loss-of-function mutations. Patients with AD can be up to three times more likely to develop an irritant contact dermatitis reaction.

Presentation

Both forms of contact dermatitis appear as inflammatory reactions on the skin. ICD is characterised by erythema and vesiculation, dryness and scaling, whereas ACD develops 24 to 72 hours after allergen exposure and the predominant symptom is pruritus. Common causes of ICD include soaps, detergents and solvents, although ACD is more likely to be due to cosmetic ingredients such as preservatives and dyes as well as metals (e.g. nickel), rubber or glues and even some plants.

Advice and treatment

Both irritant and contact dermatitis can be managed by avoidance of the responsible irritants and allergens. If this is impossible in the working environment, then wearing protective clothing such as gloves will help reduce exposure. For those with allergic contact dermatitis, it is helpful to know the specific allergens (and their synonyms) and the types of products containing these allergens so that they can be avoided.

When there is uncertainty about the potential for an allergic contact dermatitis reaction, patients should apply a small amount of the product to their forearm twice daily for up to two weeks. If this leads to an eczematous reaction, they should avoid that product.

Emollients are an important treatment for contact dermatitis because their barrier enhancing properties reduce the penetration of the allergen or irritant. Topical steroids can also be used to manage a flare-up but their use should be limited to no longer than seven days.

Altered skin microbiome

Emerging research is beginning to unravel the import-ance of the range of different microorganisms on the skin (microbiomes) for our health and well-being. It appears that there is a complex interaction between the skin barrier, immune defence and the microbiome that leads to a balance between healthy and diseased skin.

The skin surface of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) has up to twice the concentration of staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) compared to those with normal skin. Moreover, the skin pH is increased in those with AD and this favours the growth of S. aureus, which can penetrate and disrupt the skin barrier. A greater microbiome diversity is correlated with better skin health and this diversity is reduced in those with inflamed eczema.

The reasons for the greater susceptibility to infections in those with AD is unclear but may be related to an altered immune response due to toxins produced by S. aureus. Such alterations in the immune function can lead to a reduction in the endogenous production of antimicrobial peptides and a greater production of inflammatory cytokines.

Patients with atopic eczema are at an increased risk of developing impetigo and viral infections such as herpes simplex, which can lead to eczema herpeticum.

Abnormal immune function: associated problems

Vitiligo

Evidence for a possible connection between vitiligo and AE comes from several observational studies that suggest having AE increases the risk of developing both vitiligo and alopecia areata (see later). Vitiligo is an autoimmune disorder affecting between 0.5 and 2 per cent of the world population. It occurs equally in both sexes although is more commonly diagnosed in women.

Vitiligo can occur at any age but tends to first present between the ages of 10 and 30 years, with the average age at onset 20 years. It is often associated with other autoimmune disorders such as thyroid disease, Addison’s disease and diabetes.

Presentation

Vitiligo is diagnosed from the appearance of depigmented macules (flat patches) surrounded by normal skin. The depigmented regions are white in colour and are particularly obvious if the surrounding skin is darker. Lesions may be initially pruritic but generally vitiligo is asymptomatic.

The degree of depigmentation can vary from a few small and isolated patches to total loss of colour in extreme cases. The commonest sites are the face, neck, forearms, feet and the dorsal surface of the hand, fingers and scalp. Disease progression is unpredictable and can be very slow or fast.

There are two common forms of vitiligo – non-segmental and segmental vitiligo. The non-segmental form is symmetrical, affecting both sides of the body in the same place and this is the form seen in around 90 per cent of cases. The segmental form is generally more stable and develops less erratically and unilaterally.

Causes

The cause of vitiligo is due to the absence of functioning melanocytes although the underlying mechanism responsible for this loss of function remains unclear. There is a clear genetic basis and vitiligo appears to run in families for some patients.

Other factors that appear to act as triggers include skin trauma, illness, sunburn and emotional stress. Although seen in patients with AE, it is currently unclear how both conditions are related but it is possibly due to immune dysfunction.

Advice and treatment

Although incurable, available treatments for vitiligo can help to restore skin colour but this might not be permanent. Phototherapy has been used for several years although a recent review concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend any specific form of phototherapy. Other topical therapies include potent topical steroids and topical immunomodulators.

The use of high factor sunscreens is an important general protection measure that pharmacy teams should communicate to people with vitiligo, since white areas of skin will burn rather than tan.

Alopecia areata

Alopecia is a term used to describe the loss of hair from areas where it normally grows. Alopecia areata (AA) is reserved for hair loss on the head although in practice this is not restricted to the scalp and can occur in the beard area, eyebrows and eyelashes. The prevalence of AA in patients with atopic eczema has been shown to vary between 1.7 and 33 per cent (average 9.4 per cent) and estimates for the UK suggest that it affects around two in 1,000 people.

Although AA can occur at any age, most patients are affected in childhood and over 80 per cent by the age of 40 years. The condition occurs with an equal prevalence in both sexes and doesn’t appear to be any more common in different ethnic groups.

Presentation

AA normally presents with a single patch, most often on the scalp. The bald area appears smooth and is either slightly inflamed or skin-coloured. Typically, patches are oval shaped and roughly the size of a large coin. Patients with long hair may be unaware that they have developed a bald patch.

Once developed the hair will normally regrow over a period of a few months and initially appears white or grey although the normal hair colour will return over time. Patients may also experience the development of new patches while the older ones are re-growing.

Spontaneous remission can occur in up to 80 per cent of sufferers although a poorer prognosis is seen in those with a family history of the condition and atopic disease.

There are few physical problems associated with AA but the visible nature can have a negative psychosocial impact on sufferers.

Causes

The precise cause remains uncertain but much evidence points towards it being an autoimmune disease. There are no known risk factors apart from a family history, which is present in up to 20 per cent of patients. There is a suggestion that stressful life events may be related to the onset or progression of the condition.

Advice and treatment

Several different treatments have been used with varying degrees of success but none cure the underlying problem. In the first instance, it is worth reassuring patients with mild hair loss that no treatment is required and that they are likely to experience re-growth within a year. Sun safety advice is important since affected areas can easily burn. Although minoxidil is effective, the OTC product is licensed for alopecia androgenetica, which is male-pattern baldness and has a different cause to AA.

Alopecia areata normally presents with a single patch

Advice and a new approach

Patients with atopic eczema should practise simple measures such as handwashing before applying topical treatments, using clean spatulas to apply emollients from a tub or a pump dispensed product. The use of antiseptic washes or even emollients with antiseptics, such as those from the Dermol range, can help reduce the levels of S. aureus on the skin.

One approach gaining interest in the management of atopic eczema is the use of bleach bathing. This involves the use of sodium hypochlorite 2%, which is present in Milton sterilising fluid. Bleach bathing should be done two to three times a week. As a rough guide, four capfuls of the sterilising fluid in a half-filled bath is sufficient.