In OTC

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

We preen, pamper and protect our skin – with good reason. Skin, the body’s largest organ, provides a waterproof barrier against the environment, pathogens and toxins. But skin is more than an inert physical defence.

The skin produces vitamin D and contributes to immune responses. Touch, pain and several other perceptions begin in the skin. Skin also influences body temperature, fluid loss and even our self-esteem, with skin damage sometimes leading to long-lasting scarring.

According to the British Skin Foundation, 70 per cent of British people have visible skin conditions or scars that affect their confidence.

For instance, about one in 100 people in the UK live with facial scarring, which can cause an excessive preoccupation with their appearance. A loss of self-confidence and the reaction of other people can mean that they avoid social situations, which, in turn, leads to isolation. A study in the British Journal of Psychiatry Open found that people with facial scarring were particularly prone to depression and anxiety.

While scarring is irreversible, the pharmacy team can help improve the appearance of scars.

Types of scars

Scarring is as a relatively rapid way to restore the skin barrier and reduce the risk of complications, such as infections and blood loss. Typically, scarring restores the skin barrier within two to four weeks after the injury, which can be a lifesaver for people living in parts of the world with poor access to emergency healthcare, including antibiotics and dressings.

Indeed, wound dressings are increasingly sophisticated, which helps minimise scarring. For instance, active venous leg ulcers need dressings that retain moisture and, therefore, hasten healing and reduce pain and scar severity.

Foam or alginate dressings are most appropriate for wounds producing large amounts of exudate. Hydrocolloids or thin-film dressings are generally more suitable for low-exudate wounds.

So, if you think that a dressing is not meeting a person’s need – the dressing leaks, for example – suggest that the patient sees their nurse or GP.

Scars sacrifice skin structure for speedy healing and differ fundamentally from healthy skin. Scar tissue lacks certain important skin structures, such as hair follicles and sweat glands.

Scars are also less flexible and weaker than healthy skin. They regain at most 80 per cent of the strength of unwounded skin. They are rich in collagen, a protein that helps maintain the skin’s normal structure, but the arrangement of collagen in a scar differs from that in healthy skin.

Despite these common features, scars can be as individual as the patient. For example, younger people tend to show larger and thicker scars than older patients. Scars may be pink, red, purple, white or brown.

Sometimes, scars are darker than the surrounding skin. However, there are, broadly, several types of scar (see boxout).

“A moist wound speeds healing, reduces pain and lessens the chance of scarring”

From fine-line scars to stretch marks

Fine-line scars

Initially, fine-line scars, such as those from minor cuts or surgical incisions, can be slightly raised and may itch for a few months. Fine-line scars are not typically painful and usually flatten and fade over time without treatment. On darker skin, fine-line scars may leave a brown or white mark.

Atrophic scars

Atrophic scars (also called pitted or ice-pick scars) are deep, small holes in the skin similar to a deep pore. Some atrophic scars can be larger and slightly sunken. Atrophic scars usually follow acne or chickenpox. Injuries that result in the loss of fat under the skin can also cause atrophic scars.

Contracture scars

Scar tissue is stiff, dense, inelastic and tends to contract over time. In deeper wounds, the shrinking and tightening scar tissue pulls the edges together. Contracture scars, especially across joints, can make movement uncomfortable or difficult. The person may need surgery, occupational therapy or physiotherapy to maintain function. Burns are the most common cause of contracture scars.

Stretch marks

Elastin, as the name suggests, is a protein that gives skin elasticity and flexibility. Elastin returns to its original size and shape after being stretched to up to eight-times its normal length.

Despite this elasticity, stretch marks (also called striae) develop when skin stretches or shrinks too quickly, such as during rapid weight loss or gain; weight training; puberty; or pregnancy. The rapid change ruptures collagen and elastin. Stretch marks appear as the skin heals.

Steroid creams, especially potent formulations used long-term, as well as oral and high-dose inhaled steroids, can weaken collagen and elastin (thin the skin), which predisposes to stretch marks and easy bruising.

At first, stretch marks are red, purple, pink, reddish-brown or dark brown. Stretch marks may feel slightly raised and can itch. The colour slowly fades and a mature stretch mark may leave a slight depression in the skin.

Hyperproliferative scars

Sometimes, a burn, cut or another wound can ‘over-heal’, producing a hyperproliferative scar such as a hypertrophic or keloid scar. Moving an area with a hypertrophic or keloid scar may be uncomfortable or difficult. Why hypertrophic scars and keloids ‘over-heal’ is not clear.

These scars, caused by excessive collagen formation, are usually raised and firm. While hypertrophic scars are no bigger than the original wound, they may thicken for up to six months after the injury. Initially, hypertrophic scars are red or purple, but become flatter and paler over several years.

They tend to occur on areas of high skin tension, such as the outside of a joint, and some estimates suggest that more than 90 per cent of burn and surgical patients develop hypertrophic scars. So, surgeons tend to cut with, rather than against, the skin’s natural lines of tension.

Keloid scars also arise when the body produces more collagen than is needed to heal the wound. But keloid scars are benign (non-cancerous) tumours that do not stop growing and do not regress. Keloid scars can arise from lacerations, burns and even minor trauma, such as ear piercing.

Keloid scars are typically raised, hard, smooth and larger than the original wound. Initially, keloid scars are red or purple and gradually become paler. Keloid scars can be itchy and painful, and do not generally flatten without treatment. However, treating keloid scars can be difficult. Keloid scars recur after surgical removal in more than 70 per cent of cases.

Under-healing

Essentially, hypertrophic and keloid scars arise when a wound over-heals. But under-healing also causes problems. At least one in 10 of the population develops at least one chronic wound, such as venous leg or diabetic foot ulcers, which can cause considerable pain, intense itching, produce an offensive smell and heal slowly. In a UK study, published in the International Wound Journal, only 35 per cent of diabetic foot ulcers healed within 12 months.

Improving the appearance of scars

Most scars fade slowly, generally over about one to two years and sometimes longer, but they never disappear. The pharmacy team can, however, help improve the appearance of scarring.

Scar massage, for example, reduces the accumulation of scar tissue, promotes collagen remodelling, reduces itching, provides moisture and improves flexibility.

Massage does not, however, generally soften and flatten scars that are more than two years old.

The NHS suggests massaging a scar with a water-based cream (such as aqueous cream or E45 cream) for up to 10 minutes a few times each day.

The pharmacy team should remind people to avoid heavily perfumed products and massage only fully healed wounds.

Advise patients to use two fingers and massage in small circles over the length of the scar and the surrounding skin. Patients should then massage the scar up-and-down and from side-to-side, starting with light pressure and progressing to as deep and firm a pressure as they can tolerate.

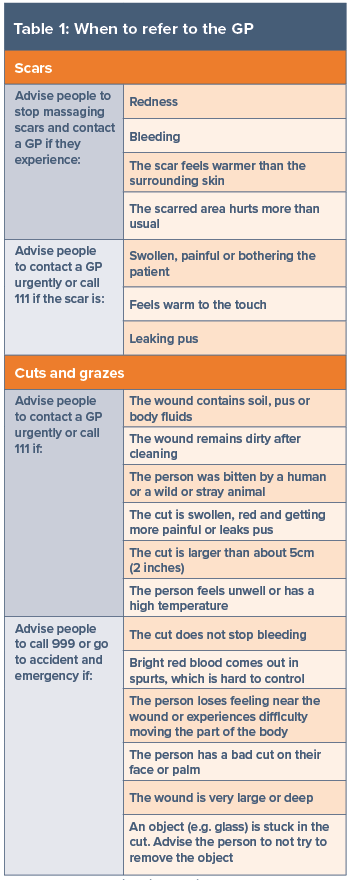

The pressure should mean that the area around the scar lightens or turns white. However, patients who experience any of the changes described in Table 1 should stop massaging their scar and seek further advice. University Hospitals Sussex produce a valuable patient information leaflet (see further support below).

In general, scars do not contain melanocytes, the cells responsible for skin colour, which means they do not tan. Nevertheless, sun exposure and other forms of inflammation may turn healing scars darker than the surrounding skin (hyperpigmentation).

Advise customers to cover a scar with clothing or a dressing for at least a year when they are in the sun. After this, you could suggest they use sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 30 or more on the scar.

Other services can help people live with scarring. For example, the NHS offers skin camouflage (creams and powders) on prescription or over-the-counter that cover the scar.

GPs can refer to a skin camouflage service. Patients can also self-refer. In addition, GPs can offer or refer patients for additional treatments like silicone dressings or gels; cryotherapy (freezes the scar); laser therapy; and steroid injections or cream.

Injecting a keloid scar with a corticosteroid can result in regression and help prevent recurrence. Talking therapy may help if living with scarring undermines the patient’s mental health.

Most scars are only skin deep, but scars can have a heavy emotional, psychological and physical toll. The pharmacy team can help reduce scar severity, improve the appearance and empower people to live a full life despite scarring.

Care of minor wounds

Thoroughly cleaning a wound reduces the risk of infection. A thin layer of an antibiotic cream or ointment helps keep the surface moist. Moisture helps white blood cells remove wound debris and carries the chemical signals (such as growth factors) that promote healing. As a result, a moist wound speeds healing, reduces pain and lessens the chance of scarring.

Caregivers, parents or patients should use a dressing and change it at least daily or when it becomes wet or dirty and apply antibiotic cream or ointment to the wound when they change the dressing. Advise caregivers, parents or patients to stop if a rash develops.

After the wound has healed sufficiently to avoid infection – for example, when a hard scab forms – exposure to the air will hasten healing. However, advise caregivers or patients to visit the GP if the wound is not healing or is red, painful, weeping, warm or swollen, which might indicate infection (refer to Table 1).

Further support

- British Association of Dermatologists (skin camouflage): bad.org.uk/pils/skin-camouflage

- Changing Faces: changingfaces.org.uk/

- Chelsea and Westminster Hospital (contracture scars): chelwest.nhs.uk/your-visit/patient-leaflets/burns/scar-tissue-and-contractures-initial-stage

- Northern Ireland Direct (scars): nidirect.gov.uk/conditions/scars

- Scar Free Foundation: scarfree.org.uk/about-scarring/living-with-scars

- University Hospitals Sussex (scars): uhsussex.nhs.uk/resources/managing-your-scar-2/.